The current scenario

The COVID-19 pandemic woke the world up from a deep slumber to the fact that threats from communicable diseases continue to exist, not only from a new set of infections but also from the ones which have been with us from times immemorial. TB in humans can be traced back to 9000 years ago, while first cases of malaria date far back into the 6

th century BC

[1,2] , and yet these diseases continue to spread, together killing more than 43.4 million people globally in 2020 & 2021 alone

[3], with millions of potential cases missed and uncounted for

[4].

Investments limited to healthcare operations (infrastructure, human and material resources) won’t be enough to tame this problem. Innovation in interventions is a necessity to maximise the world’s progression into “eradication” and “elimination”. And this is bound to come with a price tag. Active funding support is crucial in therapeutics, screening, diagnostics, and antimicrobial resistance. Total funding in malaria R&D in 2020 was US$ 619 million, falling short of the estimated US$ 851 million projected to be required to stay on track towards the Global Technological Strategy milestones

[5]. Similarly, in 2021, TB research and development funding reached the billion-dollar threshold for the first time in history. While this is a significant milestone, it is only half of what the governments committed in the 2018 United Nations High-Level Meeting on TB and is only one-fifth of the resources currently required to put the world on track to end TB

[6].

The Indian perspective – a lukewarm response

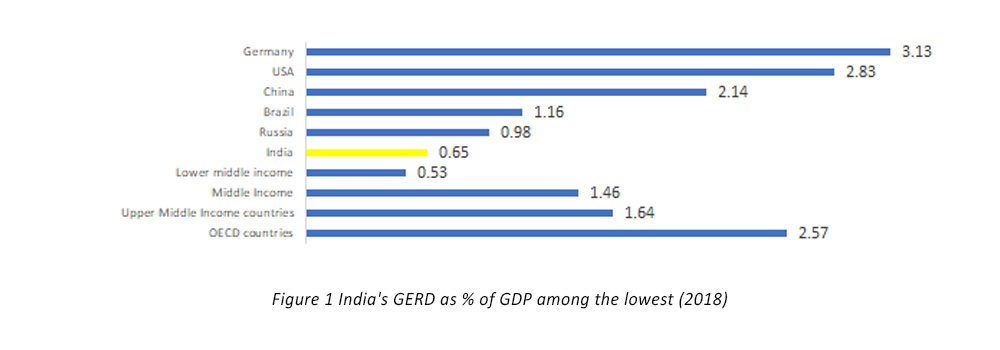

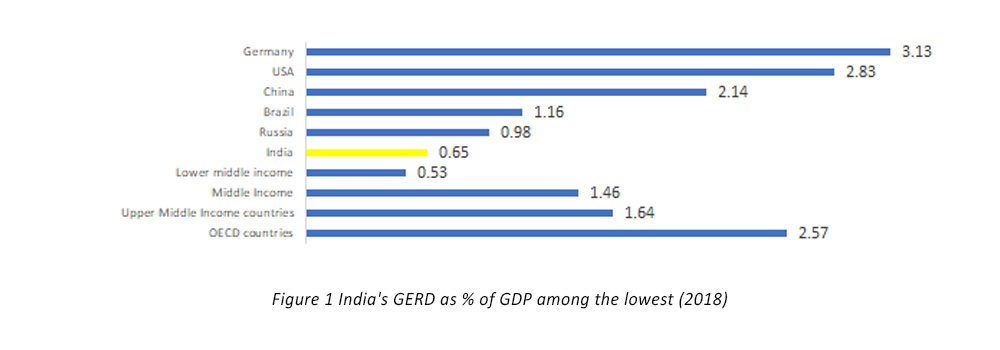

The picture in India is not any better. India’s R&D expenditure activities remain low compared to developed countries (see Figure 1). In India R&D investments hinge primarily to the expenditure undertaken by the Central government. The Economic Survey (2017-18) observed that government expenditure on R&D is undertaken majorly by the union government. There is a need for more aggressive state government spending. For instance, in 2017-18, the share of state governments’ contribution in National R&D expenditure stood at a mere 6%, of which 7 states viz. Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Assam contributed half of it

[7]. In 2021-22, expenditure by DST and DBT is estimated to be 14% and 15% lower than the budget estimates, respectively. Gross Expenditure on Research and Development (GERD) as a percentage of GDP has been declining since 2009-10

[8], with GERD in 2018-19 being a meagre 0.65% of the GDP.

This scenario in R&D is similarly replicated when it comes to expenditure for innovation in healthcare. The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2020) noted Department of Health Research’s allocation is low compared to the funds needed for health research. It recommended in 2021, that the allocation towards health research should be 5% of the total expenditure of the Ministry. The Committee reiterated its recommendations to increase the budgetary outcomes of the Department of Health Research. The Committee noted that a shortfall of funds might adversely impact the establishment of new Virology Research and Diagnostic Laboratories, Multi-Disciplinary Research Units in Medical Colleges, and Model Rural Health Research Units in states.

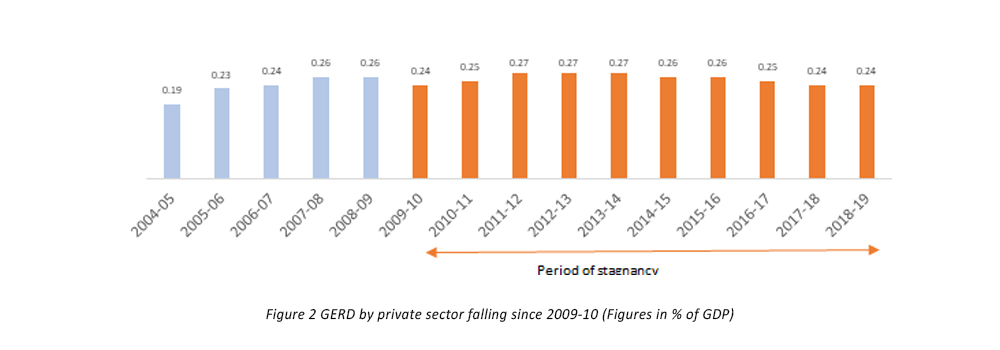

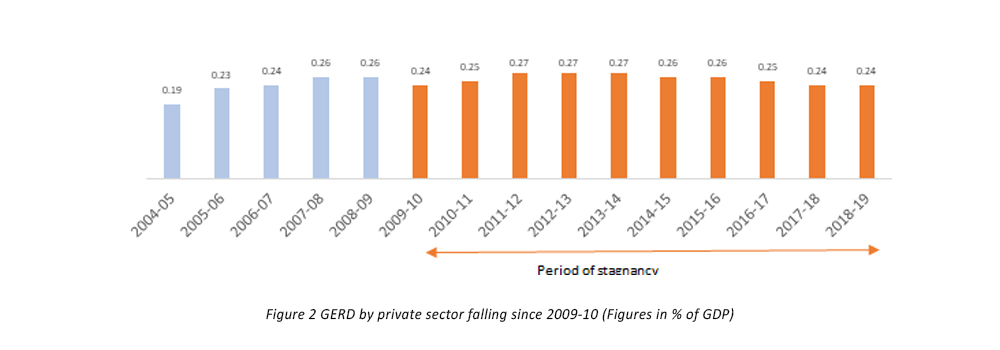

The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2017, 2018, 2021) noted the persistent mismatch between the projected demand for funds and actual allocation to the Department of Health Research. This impacted sanctioning new labs, providing regular grants to ongoing projects, and upgradation of health research infrastructure. Consequently, investments from the private sector have also suffered, with private sector expenditure (as % of GDP) on R&D remaining stagnant since 2010 . While numerous attempts have been made to buoy private-sector investments in R&D (including the allowance of CSR spending by the private sector on publicly funded incubators, research organisations and universities), the response has remained lukewarm at best.

While India continues to be the beacon for manufacturing affordable generic medicines for the world, we lag way behind when it comes to finding the next innovation be it in diagnostics, screening or therapeutics. The policies seem to move away from supporting innovations too. While we used to allow corporations 200% of weighted tax deduction i.e. tax exemption was two times the actual expenditure towards research and development. This has now dropped to 100% in April 2021. The procurement systems also tend to focus on low cost, high quantity procurements, rather than the quality of procurements for healthcare infrastructure. In fact, The Economic Survey ‘21-’22 highlighted that while L1 system (the principal of Least Cost System in procurement) may be suitable for the procurement of routine works and non-consulting services, this method may not be able to cater to the need for innovation, quality, speed and functionality for high impact, complex and technology-intensive procurements

[9].

The path ahead

Traditional financing mechanisms can no longer be relied on to cater to healthcare challenges that our world faces today. Innovators need to be compensated fairly while making sure solutions are available and affordable for the population. Gates Foundation’s Volume Guarantee solution with Merck and Bayer

[10] was an innovative approach where healthcare affordability and suppliers’ interest was ensured, thus making the whole healthcare cycle sustainable. The volume guarantee was designed as a win-win for all partners involved, including the suppliers. For donors and investors, the partnership offered a way to advance their priorities in women’s rights and access to health. By spreading the risk across partners, the exposure of any single partner was reduced.

Similarly in China, Shuidi HuZhu (Shuidi Mutual Aid) is a multi-source crowdfunding example of private insurers and a technology platform coming together to reduce financial burden. Or in Nigeria, the government funding scheme “The Nigeria Cancer Health Fund” brings together public and private stakeholders to provide a funding pathway for low-income patients to access cancer care. Such innovative financing mechanisms must become the norm if we want to go beyond business-as-usual.

Back at home, in infectious diseases, it was in 2016, that the Tata Trusts launched India Health Fund (IHF) in a strategic partnership with The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Since then, IHF’s work has supported programs and projects that develop new products or strategies for innovative business models and innovative partnerships or financing mechanisms that significantly scale existing effective solutions in public health.

We don’t have to wait for another pandemic to get our act together for finding innovative solutions that address infectious diseases. You cannot bring stick and stones to a gunfight and expect to win. We need to fund now, we need to act now. Because the bill comes due, always.

Aditya Andhansare, Associate, Fundraising and Partnerships, India Health Fund

Aditya Andhansare, Associate, Fundraising and Partnerships, India Health Fund

Aditya is a healthcare professional with an experience in M&E of digital health technologies. He has also worked extensively with capacity-building initiatives with national and state governments on M&E capacities. Aditya is a Tata Institute of Social Sciences alumni, having graduated with a Masters in Public Health with specialization in Health Policy, Economics and Finance.

References

[1] Cox, F.E. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites Vectors 3, 5 (2010)

[2] https://www.cdc.gov/tb/worldtbday/history.html

[3] Global TB Report and Global Malaria report, years 2020 & 2021

[4] https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/opinion-editorials/detail/strengthening-social-protection-for-tbpatients–lessons-from-covid-19

[5] World Malaria Report 2020 (

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791)

[6] Treatment Action Group Report (

https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/publication/2021-annual-report/)

[7] Research and Development Statistics, 2019-20, Ministry of Science & Technology, December 2020,

https://dst.gov.in/sites/default/files/Research%20and%20Deveopment%20Statistics%202019-20_0.pdf

[8] Data for lower middle-income countries is from 2017. Source: World Bank

[9] Indian Economic Survey 2021-22

[10] https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR_Healthcare_Innovative_Finance_Final_September_2017.pdf

This scenario in R&D is similarly replicated when it comes to expenditure for innovation in healthcare. The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2020) noted Department of Health Research’s allocation is low compared to the funds needed for health research. It recommended in 2021, that the allocation towards health research should be 5% of the total expenditure of the Ministry. The Committee reiterated its recommendations to increase the budgetary outcomes of the Department of Health Research. The Committee noted that a shortfall of funds might adversely impact the establishment of new Virology Research and Diagnostic Laboratories, Multi-Disciplinary Research Units in Medical Colleges, and Model Rural Health Research Units in states.

The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2017, 2018, 2021) noted the persistent mismatch between the projected demand for funds and actual allocation to the Department of Health Research. This impacted sanctioning new labs, providing regular grants to ongoing projects, and upgradation of health research infrastructure. Consequently, investments from the private sector have also suffered, with private sector expenditure (as % of GDP) on R&D remaining stagnant since 2010 . While numerous attempts have been made to buoy private-sector investments in R&D (including the allowance of CSR spending by the private sector on publicly funded incubators, research organisations and universities), the response has remained lukewarm at best.

This scenario in R&D is similarly replicated when it comes to expenditure for innovation in healthcare. The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2020) noted Department of Health Research’s allocation is low compared to the funds needed for health research. It recommended in 2021, that the allocation towards health research should be 5% of the total expenditure of the Ministry. The Committee reiterated its recommendations to increase the budgetary outcomes of the Department of Health Research. The Committee noted that a shortfall of funds might adversely impact the establishment of new Virology Research and Diagnostic Laboratories, Multi-Disciplinary Research Units in Medical Colleges, and Model Rural Health Research Units in states.

The Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare (2017, 2018, 2021) noted the persistent mismatch between the projected demand for funds and actual allocation to the Department of Health Research. This impacted sanctioning new labs, providing regular grants to ongoing projects, and upgradation of health research infrastructure. Consequently, investments from the private sector have also suffered, with private sector expenditure (as % of GDP) on R&D remaining stagnant since 2010 . While numerous attempts have been made to buoy private-sector investments in R&D (including the allowance of CSR spending by the private sector on publicly funded incubators, research organisations and universities), the response has remained lukewarm at best.

While India continues to be the beacon for manufacturing affordable generic medicines for the world, we lag way behind when it comes to finding the next innovation be it in diagnostics, screening or therapeutics. The policies seem to move away from supporting innovations too. While we used to allow corporations 200% of weighted tax deduction i.e. tax exemption was two times the actual expenditure towards research and development. This has now dropped to 100% in April 2021. The procurement systems also tend to focus on low cost, high quantity procurements, rather than the quality of procurements for healthcare infrastructure. In fact, The Economic Survey ‘21-’22 highlighted that while L1 system (the principal of Least Cost System in procurement) may be suitable for the procurement of routine works and non-consulting services, this method may not be able to cater to the need for innovation, quality, speed and functionality for high impact, complex and technology-intensive procurements [9].

While India continues to be the beacon for manufacturing affordable generic medicines for the world, we lag way behind when it comes to finding the next innovation be it in diagnostics, screening or therapeutics. The policies seem to move away from supporting innovations too. While we used to allow corporations 200% of weighted tax deduction i.e. tax exemption was two times the actual expenditure towards research and development. This has now dropped to 100% in April 2021. The procurement systems also tend to focus on low cost, high quantity procurements, rather than the quality of procurements for healthcare infrastructure. In fact, The Economic Survey ‘21-’22 highlighted that while L1 system (the principal of Least Cost System in procurement) may be suitable for the procurement of routine works and non-consulting services, this method may not be able to cater to the need for innovation, quality, speed and functionality for high impact, complex and technology-intensive procurements [9].

Aditya Andhansare, Associate, Fundraising and Partnerships, India Health Fund

Aditya is a healthcare professional with an experience in M&E of digital health technologies. He has also worked extensively with capacity-building initiatives with national and state governments on M&E capacities. Aditya is a Tata Institute of Social Sciences alumni, having graduated with a Masters in Public Health with specialization in Health Policy, Economics and Finance.

Aditya Andhansare, Associate, Fundraising and Partnerships, India Health Fund

Aditya is a healthcare professional with an experience in M&E of digital health technologies. He has also worked extensively with capacity-building initiatives with national and state governments on M&E capacities. Aditya is a Tata Institute of Social Sciences alumni, having graduated with a Masters in Public Health with specialization in Health Policy, Economics and Finance.